False news is the result of the flaws of the human condition – there might be bots and bad actors and accidents, but really it’s just who we are – according to a new study from MIT. This is one of the first studies of its kind and of its scale, and the first thing that strikes you as you read through the methodology is how well thought-out it is.

Using an impressively amassed and organised database of Twitter accounts, tweets, retweets and the like, the study pokes and prods the data from more angles that one might’ve thought existed. Perceptions are accounted for, confounding actors considered and extraneous influences isolated. How rare to see such a thing, in the modern media environment; a thing which can be considered scientific in nature – a label not offered lightly – and injected straight into the mainstream discourse.

The second thing that strikes you – as you end the methodology section to embark on the results – is that the study backs up a famous quote about the efficacy of untruths. And, in a sort of sarcastic circumstantial inconvenience, it’s a quote that’s difficult to attribute.

“A lie can travel halfway around the world before the truth can get its boots on”

– Mark Twain or Thomas Jefferson or Winston Churchill or Terry Pratchett

No matter its source, it’s potency develops on you as you read the tenth paragraph: The truth takes six times longer to reach the same number of people as a falsehood, and 20 times longer to reach its maximum penetration, which a falsehood will go on to nearly double. A truth will not diffuse as broadly or by the hands of as many unique users as a falsehood. And if you think that’s about as unequivocal a denunciation of our ability to deal in information germane to the topic at hand the next paragraph opens with the following “False political news traveled deeper and more broadly, reached more people, and was more viral than any other category of false information.”

False political news can reach twice as many people three times as fast as other types of false information.

An emergency exit might be useful here, an unconsidered intermediary variable which might describe these data. Perhaps this is because those who are interested in this kind of thing are more likely to follow similar accounts and be generally more active on Twitter. Is it possible to identify a sort of rumour bubble? Nope. “Users who spread false news had significantly fewer followers, followed significantly fewer people, were significantly less active on Twitter, were verified significantly less often, and had been on Twitter for significantly less time. Falsehood diffused farther and faster than the truth despite these differences, not because of them.”

Generally speaking, falsehoods are 70% more likely to be retweeted than facts. Left with such galvanising results the missing stepping stone between understanding these characteristics and doing something about them is the question ‘why’, why do falsehoods do so well?

By comparing a falsehood disseminated by a given account to the other tweets sent in the same time frame, the study was able to get an understanding of how novel the information in the tweeted falsehood was. This was done across thousands of examples. Falsehoods were shown to contain significantly higher levels of uniqueness.

Further, by comparing the emotion of the vocabulary in the replies to truths versus falsehoods the study revealed that falsehoods inspire greater surprise and disgust, corroborating the novelty hypothesis. While truths inspired greater sadness, joy, anticipation and trust.

The study then goes on to cover itself in a number of ways, accounting for the use of bots and the definition of “truth”, thus reasonably and significantly limiting the effect of bad actors and the bubble effect. The results remained stable across the checks and balances performed. More studies need conducting, science cannot exist in a vacuum, so our understanding can unfold over time. But this study does at least seem to be sincere, genuine and comprehensive, and thus worthy of serious consideration.

The novelty factor seems an important one, and it’s worth bearing in mind that there is nothing to suggest that this behaviour is the result of it being exhibited online. People may be slightly more willing to disseminate untruths behind some anonymity, but plenty of people on Twitter do not operate anonymously, and it’s most likely that people believe what they disseminate to be true, even if it isn’t. Further, it would be disingenuous to suggest that people do not engage in the proliferation of rumours without online tools.

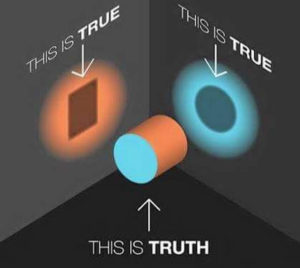

Falsehoods and rumours seem to have a headstart on facts. A fact has no care for whether it is appealing to its perceivers. A falsehood, on the other hand, can only come from the mind of someone capable of perceiving it to be plausible, and is thus far more likely to not only be appealing to the prejudices, inspirations and/or hopes of those similar to the mind from whence it came, but it is also far more likely to be coherent according to the contextual information of the mind in which it was born.

Falsehoods, therefore, are self-fulfilling prophecies in a way that facts can never be. Attempting to get the truth to be understood, as any science communicator will surely tell you, is in large part about getting people to believe that which is inconvenient or does not accord with anyone’s affinity for vindication.

So, with the ability of a given country to engage in a healthy national discourse at stake, we are now somewhat the wiser on the opposing forces. There is no care for right or left, and this study has the potential to tie itself up further in an inconvenient circumstantial sarcasm by revealing the propensity to create and believe falsehoods as a natural truth of humanity.

1 Comment